Dating the Book of Revelation

Part One

In this Learning Activity we are going to explore the topic of when the book of Revelation was written. The first question that may pop into your thinking may be: Why be concerned over such a fine point about the Bible? The answer to this question is that the date that the book of Revelation was written is a major factor in the interpretation of both the book of Revelation itself and many other passages in the Bible!

At the time of my writing of this Learning Activity, there are two camps of scholarship of the dating of the book of Revelation. One camp places the date at around the year AD 95 in the later years of the reign of the Emperor Domitian (AD 81–96). The second camp places the dating in late AD 68 prior to the destruction of Jerusalem.

The late dating (AD 95) of the book of Revelation has its roots hanging on a very slender and precarious thread. This dating is determined from a single source statement by the Bishop of Lyons by the name of Irenaeus (AD 120–202). The statement he makes is not an eyewitness testimony, but is his recollection of what was said (verbal transmission) by an earlier man, Polycarp, who is supposed to have known John (who wrote the book) personally (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, book 5, chapter 20, AD 324). The Irenaeus statement appears in his book “Against Heresies, 5:30:3″ dated AD 175–180.

Irenaeus spent his youth in Asia Minor, but his manhood and Christian work took place in Gaul, which is modern day France. It would not be a far fetched idea to think that for Irenaeus to remember a conversation from such a distant time in his life and at such an early age could have led to confusion of names and dates. This, however, is not the only basis for my personal doubts in this situation as you will see later in this material.

It appears that Irenaeus’ statements, as they were understood, shaped the opinions of Eusebius and Jerome on this question, and this view was passed on to later authors and authorities. It is my belief that it is not good scholarship to accept a dubious statement from the Bishop of Lyons that was orally transmitted to him when he was a young man. This does not appear to be adequate and compelling evidence to cause a person to set aside the overwhelming weight of evidence, both external and internal to the book of Revelation itself, as proof that the Revelation was written during the AD 95 time frame.

It is important to examine not only where and how Irenaeus came by his opinion, but also what Irenaeus said because as you will shortly see it is possible that his testimony has been misunderstood. The statement that Irenaeus makes consists of a testimony about the number of the beast, 666, in Revelation 13:18. A translation from the original Greek is as follows:

“We therefore do not run the risk of pronouncing positively concerning the name of the Antichrist [hidden in the number 666 in Rev.13:18], for if it were necessary to have his name distinctly announced at the present time, it would doubtless have been announced by him who saw the apocalypse; for it is not a great while ago that it[or he] was seen, but almost in our own generation, toward the end of Domitian’s reign.”

In this passage, it must be noted that the subject of the verb “was seen” is ambiguous in the Greek language and may be either “it” referring to the Apocalypse, or “he” referring to John himself. So the slender thread surfaces. If one chooses to select “it” meaning the vision, we have the Apocalypse being written at the later date. If “he” is chosen, meaning John, then the Apocalypse is written at the earlier date because he, John, would have been seen “almost in our own generation.” Quite a situation to base your entire “end times” prophecy doctrine on, would you not say?

From my research I am convinced that what Irenaeus was attempting to communicate was something along the following lines. John would have announced the name of the Antichrist if he wanted to because he (John) was around during the reign of Domitian. Since John did not announce it, why should we (Irenaeus and his contemporaries) run the risk of announcing it! The reason for this approach would be that although Nero was gone, Domitian and the Roman threat was still present and quite capable of carrying out a swift reprisal in the name of Rome against anyone who spoke against Nero in such a manner as to identify him as the beast!

In another place in the writing of Irenaeus, again writing about the number 666, he seems to indicate an earlier date for the dating of Revelation. In his fifth book, he writes the following: “As these things are so, and his number [666] is found in all the approved and ancient copies.” Domitian’s reign was almost in his own day, but now he writes of the Revelation being written in “ancient copies!” His statement at least gives some doubt as to the “vision” being seen in AD 95 which was almost in his day, and even suggests a time somewhat removed from his own day for him to consider the copies available to him as “ancient.”

Several of the church fathers of the third and fourth century speak of John’s writing Revelation in connection with his banishment to the Isle of Patmos, which they fix as the reign of Domitian. Yet some of them are unclear between Nero and Domitian. Clement of Alexandria says John was banished by “the tyrant,” a name appropriate to either, yet in usage applies less to Domitian and more to Nero. Tacitus, Suetonius, Pliny the Elder, and the Roman satirist Juvenal, all of whom predate Eusebius, call Nero “the proverbial tyrant.”

Eusebius, who was the bishop of Cesarea from AD 314–340, writes of John as being banished to Patmos and of seeing his visions there in the reign of Domitian. The problem with this source is that he quotes Irenaeus, in fact, the very passage we have under consideration (this appears in his history, book 3, chapter 18). He also refers to a tradition to the same effect, which may have grown out of the same leading of Irenaeus.

Jerome [331–420] held the same opinion, apparently on the authority of Irenaeus.

Victorinus of Petavio, who died in AD 303, in a Latin commentary on the Apocalypse, says “John saw this vision while in Patmos, condemned to the mines by Domitian Caesar.”

Many others of a later age could be cited supporting this same connection between John and Domitian, but it would seem that this does no more than to continue a tradition which appears to have come from the language of Irenaeus. The conclusion most come to at this point is that the external evidence of John writing the Apocalypse at the close of Domitian’s reign rests on the sole testimony of Irenaeus, who wrote a hundred years after that date, and whose words were from a verbally transmitted second source during the childhood of Irenaeus. To make matters worse, the words he used can easily have two different meanings!

Unfortunately, the earliest church fathers such as Barnabas, Clement of Rome, Papias, Polycarp and Justin Martyr, the very testimonies that would be the most helpful to us, are silent on the dating of Revelation. They either omitted this point because it was understood without their testimony, or what they wrote perished along the way.

An ancient document known as the Muratorian Canon which comes down to us from AD 170–210 states, “Paul, following the order of his own predecessor John, writes to no more than seven churches by name.” The seven churches that Paul wrote to were: Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Philippi, Colossi and Thessalonica. John, in his addressing the writing of Revelation, wrote to seven churches as indicated in Revelation 1:4. The implication of this statement in the Muratorian Canon is that John had written his book of Revelation BEFORE the completion of Paul’s writings to the seven churches he had written to. Paul died under Nero’s persecution. Nero’s rule ended in AD 68!

There is also in existence, a number of Syriac translations of the book of Revelation which have the following inscription: “The Revelation, which was made by God to John the Evangelist, in the island of Patmos, to which he was banished by Nero the Emperor.” Most of the Syriac translations, which are known as the “Peshito,” “Curetonian,” the “Philoexenian” and the “Harclean” are supposed to have been translated late in the first century or very early in the second, but the ones containing Revelation are not believed to be quite that old. The superscription on this manuscript does provide support that the dating of the Revelation goes back to the time of Nero. Moses Stuart, Commentary on the Apocalypse (1845), Vol. 1, p. 267; J. W. Mc Garvey, Evidences of Christianity (Nashville, Gospel Advocate, 1886), pp. 34,78; Milton S. Terry, Biblical Hermeneutics (1890), pp. 136, 138; James Murdock, Syriac New Testament, Peshitto Version, translated in 1852, published 1896. It is thought that the Peshitto Versions, which are dated at 150 AD, were based upon original autographs (original documents).

Clement (AD 150–215) makes the following statement supporting an early dating: “For the teaching of our Lord at His advent, beginning with Augustus and Tiberius, was completed in the middle of the times of Tiberius. And that of the apostles, embracing the ministry of Paul, end with Nero” (Miscellanies 7:17). Clement seems to indicate that he believes that the Scriptures were completed by the end of Nero’s reign which ended in AD 68.

Epiphanies, AD 315–403, stated that the book of Revelation was written under Claudius [Nero] Caesar. This Roman ruler was emperor from AD 54 to AD 68.

Andreas of Capadocia, about AD 500, in a commentary on Revelation, dates the book as Neronian.

Arethas, about AD 540 assumes the book to have been written before the destruction of Jerusalem and that its contents was prophecy concerning the siege of Jerusalem.

There is no shortage of those from the above date forward who support the earlier dating of the book of Revelation.

There is language in the book of Revelation itself that gives strong if not convincing evidence of its earlier dating. The Greek words that give us this evidence are “tachei” and “tachu.” These words appear in the following verses of Revelation.

“The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave unto him, to show unto his servants things which must shortly [tachei] come to pass; and he sent and signified [it] by his angel unto his servant John” (Rev.1:1).

“Repent; or else I will come quickly [tachu], and will fight against them with the sword of my mouth” (Rev.2:16).

“Behold, I come quickly [tachu]: hold that fast which thou hast, that no man take thy crown” (Rev.3:11).

“And he said unto me, These sayings [are] faithful and true: and the Lord God of the holy prophets sent his angel to show unto his servants the things which must shortly [tachei] be done” (Rev.22:6).

“Behold, I come quickly [tachu]: blessed [is] he that keepeth the sayings of the prophecy of this book” (Rev.22:7).

“And behold, I come quickly [tachu]; and my reward [is] with me, to give to every man according as his word shall be” (Rev.22:12).

“He which testifieth these things saith, Surely I come quickly [tachu]. Amen. Even so, come, Lord Jesus” (Rev.22:20).

These words, in their various tenses, are translated as “shortly,” and “quickly.” The words do not mean “soon,” in the sense of “sometime,” but rather “swift,” “now,” “immediately,” “hastily,” and “suddenly.” The word meanings here are critical to understanding the “imminency” that is being communicated in the vision of the book! The vision is NOT something that would be expected to take place two thousand, or more years into the future!

Another word that reeks of the imminency of the revelation to John is the Greek word “eggus” which means “at hand” or “near.” This word is found in the following passages.

“…for the time is at hand (eggus). (Rev.1:3).

“…for the time is at hand (eggus). Rev.22:10.

Another word we should look into is the Greek word “mello,” and “mellei.” These words appear in the following texts.

“Write the things which thou hast seen, and the things which are, and the things which shall [mellei] be hereafter” (Rev.1:19).

“Because thou hast kept the word of my patience, I also will keep thee from the hour of temptation, which shall [mello] come upon the world, to try them that dwell upon the earth” (Rev.3:10).

The meaning of these words are given to us as: “is about to come.” When these words are used with the aorist infinitive the preponderance of use and preferred meaning is “be on the point of, be about to.” The same is true when these words are used with the present infinitive. The basic meaning in both Thayer’s and Abbott–Smith is “to be about to” and the word “mellei” with the infinitive expresses imminence such as the immediate future. This causes us to understand that the word usage in Rev.1:19 and 3:10 portray an expectation of soon or quick future occurrence.

This kind of language should lead us to conclude that the prophecy in the vision was something that was to take place very close to its being revealed to John! I see this as being fulfilled by the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70.

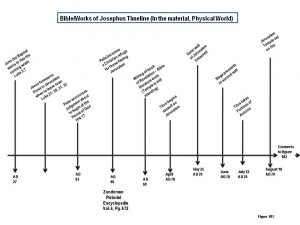

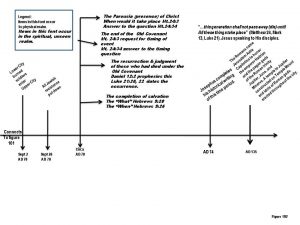

I have found that it to be helpful to have a chronological timeline to refer to when reading and studying the Bible. The two figures that follow below have been helpful to me and I include them here for your consideration.

If you click your mouse on the drawings above they will increase in size which is helpful. Click on the back arrow to return to document.

If you click your mouse on the drawings above they will increase in size which is helpful. Click on the back arrow to return to document.